As the first snow of the season comes drifting down from a sky grey as concrete, my thoughts turn to the inviting islands of the tropics. Scattered between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn are some of the most fascinating and mysterious places on the planet. Isolation in time and space has caused the rapid radial evolution of unique and diverse forms of island life, to the benefit of documentary filmmakers the world over. Charismatic presenters with well-funded television crews have brought the volcanic craters of the Galápagos Archipelago with its giant tortoises and the enigmatic orangutans of steamy Borneo into our homes. The existence of the idiosyncratic lakes of Palau was arcane knowledge once, their masses of harmless jellyfish that nourish photosynthetic bacterial gardens by following the path of the sun by day, and descending into the nutrient rich depths at night, being only of interest to science. These days, organized dives at Jellyfish Lake are big business. In the 21st century, we have become complacent. Once an island has featured on a season of Survivor, the mystique is gone. The Philippines, The Azores, The Comoros, Zanzibar, Tasmania, Fiji, Malabo, The Island of Hispaniola, all of these still hold great treasures to discover: if you care to look past the trappings of tourism, past the generic resorts, the casinos and beach parties, this is where you will find Beauty.

The warm haze of a daydream sets off neuronal synapses. Pressure drops. Temperature rises. I find myself on three of my favourite islands. Look.

Madagascar. The world's fourth largest island; its vastness is not to be underestimated. Madagascar is so diverse, so strange, the archetype of curious islands, really. Apart from its bounty of lemurs, chameleons and rare bird species, it is also a centre of endemism of the vegetable kind. Weird vegetables, at that. The Avenue of the Baobabs at sunset is a heart-stopping sight. Smooth glowing trunks standing tall and fat and healthy against the orange sky. Please ignore the rotting stumps of fallen giants, cut down for some counterintuitive, senseless reason. Madagascar is home to seven species of this special tree, six of which are found nowhere else. Waxy white Angraecum orchids festoon its forests and jagged limestone outcrops. The arid south is the location of a unique spiny thicket, pictured here. Baobabs are not the only succulents that give the impression that they were planted upside down. Swollen caudiciform shrubs abound in the Ifaty Spiny Forest, storing moisture during the long wait for monsoon rain. Didiearas thrust their thorny branches into the hot sky, looking like burnt ghosts, inspiring legends, demanding worship. However, the green cathedrals of Madagascar are slowly slipping away from us. These wonderful riches are being destroyed by mining, erosion, through agriculture, deforestation and apathy.

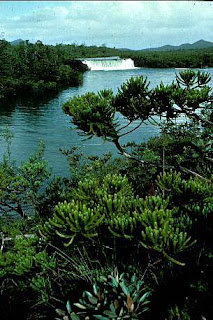

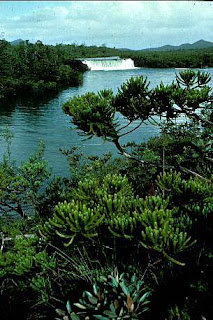

Madagascar. The world's fourth largest island; its vastness is not to be underestimated. Madagascar is so diverse, so strange, the archetype of curious islands, really. Apart from its bounty of lemurs, chameleons and rare bird species, it is also a centre of endemism of the vegetable kind. Weird vegetables, at that. The Avenue of the Baobabs at sunset is a heart-stopping sight. Smooth glowing trunks standing tall and fat and healthy against the orange sky. Please ignore the rotting stumps of fallen giants, cut down for some counterintuitive, senseless reason. Madagascar is home to seven species of this special tree, six of which are found nowhere else. Waxy white Angraecum orchids festoon its forests and jagged limestone outcrops. The arid south is the location of a unique spiny thicket, pictured here. Baobabs are not the only succulents that give the impression that they were planted upside down. Swollen caudiciform shrubs abound in the Ifaty Spiny Forest, storing moisture during the long wait for monsoon rain. Didiearas thrust their thorny branches into the hot sky, looking like burnt ghosts, inspiring legends, demanding worship. However, the green cathedrals of Madagascar are slowly slipping away from us. These wonderful riches are being destroyed by mining, erosion, through agriculture, deforestation and apathy. New Caledonia. South of Vanuatu in the Pacific Ocean lies the French territory of Nouvelle-Calédonie. It is small in comparison to the mighty Madagascar, but is just as bountiful and diverse. And just as threatened. The kagu, a unique blue ground-living bird, has become the icon of New Caledonia nature conservation. At first glance New Caledonia is anything but exceptional among tropical islands. It straddles the Tropic of Capricorn, and like so many South Seas islands receives storms brought by the trade winds. It is surrounded by azure shallows perfect for reef diving with dugongs. It also has some old growth pine forests. Wait - pine forests? Aren't those particular to colder climes? Indeed. But you see: New Caledonia is our last precious example of the magnificent forests that must have covered much of the continent of Antarctica millions of years ago. It's hard to imagine that Antarctica was ever green, but the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana certainly was. As it broke apart and Africa and Australia drifted west and east, New Caledonia was sent out into the South Pacific, carrying its coniferous gift. The gymnosperms of New Caledonia are an exclusive club - all 43 species are endemic, occuring only there - and quite a mixed bunch. There are 18 kinds of Podocarpus, 6 cypress species, a yew and nearly half of the world's araucarias, those Jurassic evergreens sometimes referred to as 'monkey-puzzle' trees. Some of these trees survive in such small numbers and are so sensitive to climate change that their continued survival seems jeopardized. Will we go on losing things we never even knew we had? The French refer to one of the smaller islands in the New Caledonia archipelago as 'l'île la plus proche du paradis', which means 'the closest island to paradise'. Its name is the Isle of Pines.

New Caledonia. South of Vanuatu in the Pacific Ocean lies the French territory of Nouvelle-Calédonie. It is small in comparison to the mighty Madagascar, but is just as bountiful and diverse. And just as threatened. The kagu, a unique blue ground-living bird, has become the icon of New Caledonia nature conservation. At first glance New Caledonia is anything but exceptional among tropical islands. It straddles the Tropic of Capricorn, and like so many South Seas islands receives storms brought by the trade winds. It is surrounded by azure shallows perfect for reef diving with dugongs. It also has some old growth pine forests. Wait - pine forests? Aren't those particular to colder climes? Indeed. But you see: New Caledonia is our last precious example of the magnificent forests that must have covered much of the continent of Antarctica millions of years ago. It's hard to imagine that Antarctica was ever green, but the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana certainly was. As it broke apart and Africa and Australia drifted west and east, New Caledonia was sent out into the South Pacific, carrying its coniferous gift. The gymnosperms of New Caledonia are an exclusive club - all 43 species are endemic, occuring only there - and quite a mixed bunch. There are 18 kinds of Podocarpus, 6 cypress species, a yew and nearly half of the world's araucarias, those Jurassic evergreens sometimes referred to as 'monkey-puzzle' trees. Some of these trees survive in such small numbers and are so sensitive to climate change that their continued survival seems jeopardized. Will we go on losing things we never even knew we had? The French refer to one of the smaller islands in the New Caledonia archipelago as 'l'île la plus proche du paradis', which means 'the closest island to paradise'. Its name is the Isle of Pines.

Socotra. Look at a map of Africa. Scrutinize the area known as the Horn of Africa, that landmass jutting into the Indian Ocean just south of the Arabian Peninsula. See the little island there, as if the tip of the Horn had broken off? You've located Socotra, Yemen's largest island. And bizarre it is, too. Its 40 000 inhabitants speak Socotri, supposedly derived from the language spoken by the Queen of Sheba. It can be classified as a tropical desert, with more than 300 plant species being endemic. Of these, nine whole genera of plants are found there and nowhere else. That's an amazing amount of biodiversity. This is what evolution does when an island is separated from the mainland for 20 million years. Socotra has forests of Boswellia, a small tree that produces the aromatic resin known as frankincense. Similar to the dry forests of Madagascar, the unforgiving climate compels many plants to conserve moisture. Swollen stems sprout from the gritty soil, their contorted branches remaining leafless for much of the year. A lunar forest. One of these caudiciforms is Dendrosicyos socotrana, the only member of the Cucurbitaceae (which includes squash, melons, pumpkins and cucumbers) to have graduated from that lowly life into the grand stature of a tree. It is on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Probably the most emblematic of Socotran botanical curiosities is the Dragon's Blood tree, Dracaena cinnabari, pictured here. This is the same genus as the familiar office plant fodder and little green pieces of so-called 'lucky bamboo' sold in florists. It is definitely not a true bamboo (which is a member of the vast family of grasses), and is more closely related to the agaves of the New World. When wounded, the trunk of this remarkable plant weeps a bright red sap, the mythical 'dragon's blood'. Highly prized in the ancient world, it was used as a panacea to cure almost everything, from fever to skin disorders and stomach ailments. The skillful Italian violinmakers of the 18th century used it as a source of dark red varnish for the most exceptional of their instruments. Although protected by CITES, many of Socotra's interesting and useful plants are under threat from overgrazing and human development. Will this distruction be the theme that ties all the places of secret beauty together? When will we realize that it is the Beauty of nature that has always been the secret inspiration behind all of our endeavours, our technology, our poetry?

here is the deepest secret nobody knows

(here is the root of the root and the bud of the bud

and the sky of the sky of a tree called life; which grows

higher than the soul can hope or mind can hide)

and this is the wonder that's keeping the stars apart

i carry your heart (i carry it in my heart)

- e.e. cummings